This is at a local tattoo shop, Diamond Tattoos. You can check out their myspace page at myspace.com/diamondtattoostudio

It is apparent that tattooing was widely practiced in many cultures in the ancient world and was associated with a high level of artistic endeavor. The imagery of ancient tattooing is very similar to that of modern tattooing.

Throughout history, tattooing, like other forms of body decoration, has been related to the sensual, erotic, and emotional aspects of the psyche. Inca tattooing is characterized by bold abstract patterns that resemble contemporary tribal tattoo designs. Pazyryk tattoos are images of animals. Animals are the most frequent subject matter of tattooing.

In many cultures tattoos are traditionally associated with magic, totems, and the desire of the tattooed person to become identified with the spirit of the animal. Tattooing in the ancient world had many things in common with modern tattooing, and tattooing around the world has profound and universal psychic origins.Upper Paleolithic (10,000 to 38,000 BC)

Tattoo instruments from this period have been found and typically these instruments consist of a disk made of clay and red ochre together with sharp bone needles that are inserted into holes in the top of the disk. The disk served as reservoir and source of pigment, and the needles were used to pierce the skin. Clay and stone figurines with engraved designs, which probably represent tattooing, have also been found.

European Iceman Mummy

A Bronze Age tattooed man around 5,500 years old was found in October 1991

between Austria and Italy in the Tyrolean Alps. The Iceman, "Oetzi" is the

oldest known human to have medicinal tattoos preserved upon his mummified skin.

The God Bes

The earliest known tattoo with a picture of something specific, rather than an abstract pattern, represents the god Bes. Bes is the lascivious god of revelry and he served as the patron god of dancing girls and musicians. Bes’s image appears as a tattoo on the thighs of dancers and musicians in many Egyptian paintings, and Bes tattoos have been found on female Nubian mummies dating from about 400BC.

Greek Times

Tattooing was only associated with barbarians in early Greek and Roman times. The Greeks learned tattooing from the Persians, and used it to mark slaves and criminals so they could be identified if they tried to escape. The Romans in turn adopted the practice from the Greeks, and in late antiquity when the Roman army consisted largely of mercenaries; they also were tattooed so that deserters could be identified.

Many Greek and Roman authors mentioned tattooing as punishment. Plato thought that individuals guilty of sacrilege should be tattooed and banished from the Republic.

Suetone, a early writer reports that the degenerate and sadistic Roman Emperor, Caligula, amused himself by capriciously ordering members of his court to be tattooed.

According to the historian, Zonare, the Greek emperor, Theophilus, took

revenge on two monks who had publicly criticized him by having eleven verses of

obscene iambic pentameter tattooed on their foreheads.

Africa!

A form of tattooing called cicatrisation or scarification is widely practiced in traditional African societies. Rubbing charcoal into small cuts made with razors or thorns forms decorative patterns of scar tissue in the skin. These designs are often indicative of social rank, traits of character, political status and religious authority. For African women, scarification is largely associated with fertility. Scars added at puberty, after the birth of the first child, or following the end of breastfeeding highlight the bravery of women in enduring the pain of childbirth. Scars on the hips and buttocks, on the other hand, both visually and tactually accentuate the erotic and sensual aspects of these parts of the female body.

Some early African fertility carvings had symbols on them that may be tattoos.

South American Tattooing

(Peru) 11th Century

In 1920, archaeologists in Peru unearthed tattooed mummies dating from the 11th Century AD. Not much is known about the significance of tattooing within the culture of pre-Incan peoples like the Chimu who tattooed, but the elaborate nature of the designs suggests that tattooing underwent a long period of development during the pre-Inca period.

The Chimú of Pre-Columbian Peru applied tattoo pigments with various types of needles (fishbone, parrot quill, spiny conch) which have been found in mummy burials. The technical application of tattooing was a form of skin-stitching, and it has been suggested that women were the primary tattoo artists.

A History of Japanese Tattooing

5,000 BC

The earliest evidence of tattooing in Japan is found in the form of clay

figurines that have faces painted or engraved to represent tattoo marks. The

oldest figures of this kind have been recovered from tombs dated to 5,000 BC or

older.

297 AD

297 AD

The first written record of Japanese tattooing is found when a Chinese dynastic

history was compiled. According to the text, Japanese "men young and old, all

tattoo their faces and decorate their bodies with designs." Japanese tattooing

is also mentioned in other Chinese histories, but always in a negative context.

The Chinese considered tattooing a sign of barbarism and used it only as

punishment.

7th Century

By the early seventh century, the rulers of Japan had adopted much of the

culture and attitudes of the Chinese, and as a result decorative tattooing fell

into official disfavor.

720AD

The first record of Japanese tattooing as punishment was mentioned in a history.

that reads: "The Emperor summoned before him Hamako, Muraji of Azumi and

commanded him saying: You have plotted to rebel and overthrow the state. This

offence is punishable by death. I shall, however, confer great mercy on you by

remitting the death penalty and sentence you to be tattooed."

17th

Century

17th

Century

By the early seventeenth century, there was a generally accepted codification of

tattoo marks used to identify criminals and outcasts in Japan. Outcasts were

tattooed on the arms: a cross might be tattooed on the inner forearm, or a

straight line on the outside of the forearm or on the upper arm.

Criminals were marked with a variety of symbols that designated the places where the crimes were committed. In one region, the pictograph for "dog" was tattooed on the criminal’s forehead. Other marks included patterns which included bars, crosses, double lines, and circles on the face and arms. Tattooing was reserved for those who committed serious crimes, and individuals bearing tattoo marks were ostracized by their families and denied all participation in community life. For the Japanese, tattooing was a very severe and terrible form of punishment.

By the end of the seventeenth century, penal tattooing had been largely replaced by other forms of punishment. One is reason is that decorative tattooing became popular, and criminals covered their penal tattoos with larger decorative tattoos. This is also thought to be the historical origin of the association of tattooing and organized crime in Japan.

The earliest reports of decorative tattooing are found in fiction published toward the end of the seventeenth century.

18th Century

Pictorial

tattooing flourished during the eighteenth century in connection with the

popular culture of Edo, as Tokyo was then called. Early in the 18th century,

publishers needed illustrations for novels, theatres needed advertisements for

their plays and the Japanese wood block print was developed to meet these needs.

The development of the wood block print parallels, and had great influence on,

the development of tattooing. Because of the association between tattooing and

criminal activity, tattooing was outlawed on the grounds that it was "deleterious

to public morals."

Pictorial

tattooing flourished during the eighteenth century in connection with the

popular culture of Edo, as Tokyo was then called. Early in the 18th century,

publishers needed illustrations for novels, theatres needed advertisements for

their plays and the Japanese wood block print was developed to meet these needs.

The development of the wood block print parallels, and had great influence on,

the development of tattooing. Because of the association between tattooing and

criminal activity, tattooing was outlawed on the grounds that it was "deleterious

to public morals."

Tattooing continued to flourish among firemen, laborers and others considered to be at the lower end of the social scale. Tattoos were favored by gangs called Yakuza, outlaws, penniless peasants, laborers and misfits who migrated to Edo in the hope of improving their lives.

The Yakuza felt that because tattooing was painful, it was a proof of

courage; because it was permanent, it was evidence of lifelong loyalty to the

group; and because it was illegal, it made them outlaws forever.

The Yakuza felt that because tattooing was painful, it was a proof of

courage; because it was permanent, it was evidence of lifelong loyalty to the

group; and because it was illegal, it made them outlaws forever.

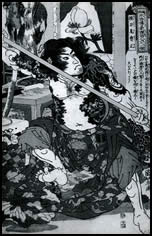

Around the middle of the 18th century, the popularity of tattooing was stimulated by a popular Chinese novel, Suikoden, with many of its novel’s heroes extensively tattooed. The Japanese version of Suikoden was illustrated by a variety of artists, each of whom created prints with new interpretations of the tattoos described in the novel.

This novel and the new illustrations influenced all Japanese arts and culture.

19th Century

By

1867, the last of the Tokugawa shoguns was deposed and an emperor was restored

to power. The laws against tattooing were strictly enforced because the new

rulers feared that Japanese customs would seem barbaric and ridiculous to

Westerners. Ironically, under the new laws Japanese tattoo artists were allowed

to tattoo foreigners but not Japanese. The best tattoo masters established

studios in Yokohama and did a lot of business tattooing foreign sailors. Their

skills were so great that they attracted a number of very distinguished clients

including the Duke of York (Later King George V), the Czarevich of Russia (Later

Czar Nicholas II), and other European dignitaries.

By

1867, the last of the Tokugawa shoguns was deposed and an emperor was restored

to power. The laws against tattooing were strictly enforced because the new

rulers feared that Japanese customs would seem barbaric and ridiculous to

Westerners. Ironically, under the new laws Japanese tattoo artists were allowed

to tattoo foreigners but not Japanese. The best tattoo masters established

studios in Yokohama and did a lot of business tattooing foreign sailors. Their

skills were so great that they attracted a number of very distinguished clients

including the Duke of York (Later King George V), the Czarevich of Russia (Later

Czar Nicholas II), and other European dignitaries.

The Japanese tattoo masters also continued to tattoo Japanese clients

illegally, but after the middle of the 19th century, their themes and techniques

remained unchanged. Classical Japanese tattooing is limited to specific designs

representing legendary heroes and religious motifs which were combined with

certain symbolic animals and flowers and set off against a background of waves,

clouds and lightning bolts.

The Japanese tattoo masters also continued to tattoo Japanese clients

illegally, but after the middle of the 19th century, their themes and techniques

remained unchanged. Classical Japanese tattooing is limited to specific designs

representing legendary heroes and religious motifs which were combined with

certain symbolic animals and flowers and set off against a background of waves,

clouds and lightning bolts.

The original designs used in Japanese tattooing were created by some of the best ukiyoe artists. The tattoo masters adapted and simplified these designs to make them suitable for tattooing, but didn’t invent the designs on their own.

Traditional Japanese tattoo differs from Western tattoos in that is consists of a single major design that covers the back and extends onto the arms, legs and chest. The design requires a major commitment of time, money and emotional energy.

During most of the 19th century, an artist and a tattooist worked together.

The artist drew the picture with a brush on the customer’s skin, and the

tattooist just copied it.

During most of the 19th century, an artist and a tattooist worked together.

The artist drew the picture with a brush on the customer’s skin, and the

tattooist just copied it.

20th Century

In 1936, when fighting broke out in China, almost all the men were drafted into

the army. People with tattoos were thought to be discipline problems, so they

weren’t drafted and the government passed a law against tattooing. After that

the tattooists had to work in secret. After WWII, General MacArthur liberalized

the Japanese laws, and tattooing became legal again. But the tattoo artists

continued to work privately by appointment, and this tradition continues today.

The early Christian and Moslem era brought a temporary halt to widespread

tattooing in Europe and the Middle East. In the Old Testament of the Bible, the

book of Leviticus states, "Ye shall not make any cuttings in your flesh for the

dead, nor print any marks upon you: I am the Lord." The problem, it seems, was

one of religious competition. The rites of tattooing were a trade mark of the

earlier religions in Palestine. When the early Jews tried to ban the marks of

their religious competitors (the Arabs and Christians) they crippled the art of

tattooing through two millennia. The edict against tattooing gained the favor of

Rome and the power of Islam, because the Old Testament is revered by both the

Christians and the Moslems.

|

|

Moslem pilgrims visiting Mecca and Medina also received commemorative tattoos. These Moslem pilgrims believed that, by being cremated at death, they would be purified by fire, before entering paradise.

Jewish Religious Tattoos

There is a passage in the Old Testament that prohibits tattooing and scarification. In the King James translation, Leviticus 19:28 states: “Ye shall not make any cuttings in your flesh for the dead, nor print any marks upon you.” Other historical records and biblical passages indicate that ancient Hebrews practiced religious tattooing.

|

|

As evidence of tattooing among Semites, Scutt and Gotch report that the sun god Baal required his worshipers to mark their hands with “divine tokens in a mystic attempt to acquire strength.” Scutt, R.W.B. and Gotch, C. 1986, Art, Sex and Symbol. London: Cornwall Books, p.64

According to a biblical scholar William McClure Thomson, Moses “either instituted such a custom (tattooing) or appropriated one already existing to a religious purpose. Thomson quotes Exodus 9 & 16: “And thou shalt show thy son in that day, saying, this is done because of that which the Lord did unto me when I cam forth out of Egypt; and it shall be for a sign unto thee upon my hand, and for a memorial between thine eyes.” Thomas theorizes that Moses borrowed tattooing from the Arabs who tattooed magical symbols on their hands and foreheads.